Indonesia has named Suharto a national hero, reopening long-simmering wounds from one of Southeast Asia’s darkest chapters. Supporters call him a stabilizing force. Survivors say it is an injustice that rewrites history.

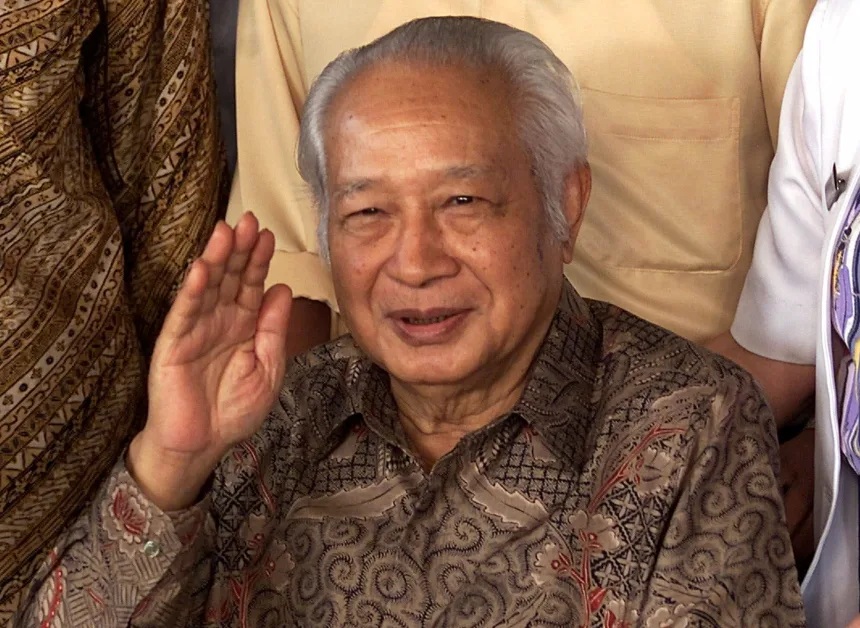

For many Indonesians, Suharto is a name that evokes both rapid development and extraordinary suffering. His 31-year rule shaped a generation, defined a region, and left deep scars that have never fully healed. So when Indonesia’s government announced this week that the former president would be posthumously honoured as a national hero, the decision did more than stir debate. It reignited a national argument over memory, accountability, and the uneasy balance between pride and pain.

The award was conferred by President Prabowo Subianto, a figure whose connection to Suharto is personal as well as political. A former special forces commander, Prabowo once served under Suharto’s rule and was married to his daughter. His own military career is shadowed by allegations of rights abuses during the turbulent final years of the Suharto era. Against that backdrop, critics say the decision to recognize Suharto is loaded with symbolism that goes far beyond a mere ceremonial honour.

The official line presented Suharto as “a hero of the struggle for independence,” highlighting his military career in the post-colonial years. But that portrayal glosses over the period that most defines his legacy: the bloodshed of 1965 and the iron-fisted rule that followed.

A TROUBLING LEGACY

Suharto was born in 1921, during the final decades of Dutch colonial rule. After Indonesia gained independence in 1949, he climbed the ranks of the armed forces, eventually becoming a five-star general. His path to power came through crisis. In late 1965, after a failed coup left several generals dead, Suharto blamed the incident on the Communist Party of Indonesia. What followed remains one of the most violent episodes of the 20th century in Southeast Asia, a region which was the stage for immense suffering and widescale atrocities during the 1960s and 1970s, in places from Cambodia and Laos to Vietnam and, to a lesser extent, even Malaysia and Singapore.

In Indonesia, a nationwide purge swept across the archipelago in the mid-1960s, targeting alleged communists, left-leaning activists, and in many cases, ethnic Chinese communities who were associated – often unfairly – with leftist politics. Estimates vary widely, but historians and human rights groups commonly cite a death toll between 500,000 and one million people. Declassified US government documents show that Washington viewed the killings as a strategic victory during the Cold War, offering material support, funds, and intelligence. American diplomats noted the speed and scale of the crackdown with barely concealed approval.

By 2016, an international tribunal at The Hague concluded that the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia were all complicit in what it described as crimes against humanity. Indonesia itself has never formally confronted the killings, and survivors still speak of stigma, discrimination, and decades of silence.

Suharto’s rise ushered in what became known as the New Order. It was a period marked by strict control over dissent, powerful security forces, and centralized economic planning. His government invaded or tightened its grip on contested territories including East Timor, Aceh, and West Papua, often with Western support from allies keen to back a staunch anti-communist.

CONFLICTING PERSPECTIVES

Yet Suharto’s legacy is not viewed solely through the lens of repression. Supporters credit him with steering Indonesia toward modernization, building infrastructure, and maintaining relative political stability. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Indonesia recorded rapid economic growth. For some, these achievements overshadow the brutality that underpinned his rule.

But the image of steady leadership was tarnished by entrenched corruption. Suharto’s family built vast business empires, and estimates suggest that billions of dollars in state funds were diverted toward personal and political interests. Public resentment grew steadily, but it was the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 that toppled the regime. With the rupiah collapsing and protests erupting nationwide, Suharto resigned in 1998, bringing an end to one of the world’s longest-running authoritarian governments.

In the years that followed, efforts were made to hold members of the Suharto family accountable. Some of his children faced corruption charges, and in 2015 the Supreme Court ordered the family to repay millions in embezzled public funds. Suharto himself, however, evaded any reckoning. Ill health shielded him from prosecution in his final years, and he died in 2008 denying all wrongdoing.

Given this history, the decision to elevate him to national hero status has struck many as an attempt to rewrite or sanitize the past. For families of victims, the honour feels like an erasure of their suffering. One activist, Bedjo Untung, who was imprisoned without trial for nearly a decade after the 1965 purges, spoke of the shock, anger, and lingering trauma that the announcement triggered. For survivors, the pain is not distant history – it is a daily reminder of lives upended and families shattered.

Human rights advocates have expressed similar alarm. Amnesty International criticized the move as a distortion of historical truth, while Human Rights Watch warned that the award reflects a growing trend of impunity. Andreas Harsono, the organization’s Indonesia researcher, argued that the failure to hold Suharto and his generals accountable paved the way for the whitewashing now taking place under Prabowo.

There is also a political dimension that critics say is impossible to ignore. Prabowo’s presidency has already seen the military take on expanded roles in areas traditionally reserved for civilians. Observers worry that this signals a drift back toward Suharto-era militarism – a concern amplified by the symbolic weight of the new national hero designation.

Meanwhile, Suharto’s defenders maintain that the honour is justified. His daughter, Siti Hardijanti Rukmana, said nothing was being concealed and expressed gratitude for the recognition. In regions such as Kemusuk, Suharto’s birthplace, his image remains woven into local identity. Museums, memorabilia, and souvenirs celebrate him as a strong leader who guided Indonesia through turbulent times.

This split reflects a broader reality: discussion of Suharto’s legacy remains sensitive, sometimes taboo, and clouded by bitterly competing narratives. Indonesia has made significant democratic gains since 1998, but its reckoning with the past has been incomplete, critics say. Transitional justice efforts have stalled, official apologies have been debated but never delivered, and textbooks often present sanitized versions of events. In that vacuum, different versions of history take root.

For many Indonesians, especially younger generations, Suharto is remembered as a symbol of order, stability, and economic progress. For others, he represents repression, violence, and a state that once turned against its own citizens. The new national hero title does not resolve this divide – if anything, it widens it.

As Indonesia wrestles with the meaning of this decision (and deals with the backlash), the question remains: what does it say about the country’s present that it is re-elevating a figure synonymous with one of its darkest periods? The answer depends on where one stands. But for survivors and families of victims, one truth is beyond dispute: justice was never served, and the wounds left by Suharto’s rule have never closed.

The debate over his legacy is far from over. And with this latest move, Indonesia now finds itself confronting not only the past, but the story it chooses to tell about itself in the years ahead.

Sources: CNN Asia; Reuters; Associated Press; Human Rights Watch; Amnesty International; 2016 International People’s Tribunal findings; US declassified documents (2017).