Many Malaysians under 40 – and most expats who arrived in the past few decades – may not know that Peninsular Malaysia once operated on GMT+7. A recent comment by a minister has renewed interest in whether the country is in the “right” time zone after all.

Did you know that up until 1982, Peninsular Malaysia did not operate on GMT+8 as it does today? It may surprise younger Malaysians, or anyone who moved here within the last 40 years, that the Peninsula’s clocks were once more closely aligned with Thailand and western Indonesia. That all changed on January 1, 1982, when the government moved Peninsular Malaysia forward to match Sabah and Sarawak, creating one national time zone. Interestingly, it was actually the second time the clocks had been notably shifted.

Before 1905, time in then-Malaya was largely a local consideration, with various time zones scattered haphazardly throughout the land. (In fact, at one point, Kuala Lumpur’s local time was GMT+6.46!) An effort to standardize time grew over the years, and by 1905, it had largely been set at GMT+7. After the Japanese occupation and the end of World War II, the Peninsula’s time was set at UTC+7.30 in 1945, where it remained until the final day of 1981. Finally, the clocks of the Peninsula were brought forward by half an hour on January 1, 1982, by then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, in order to synchronize Peninsular Malaysia with the Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak.

The Singapore government at the time said it followed suit to “avoid inconvenience to businessmen and travellers.” (The statement’s outdated gender-exclusivity of those working in business was not lost on commenters in social media chats!)

The 1982 decision unquestionably achieved its goal of a unified clock, but more than four decades later, questions about whether Malaysia’s current time zone is ideal have resurfaced. A light, offhand comment about early sunlight during a morning run in Kota Kinabalu recently brought the debate back into public view, drawing thousands of reactions and reviving a long-standing discussion about health, daylight, and daily routines.

HOW THE DEBATE FLARED UP AGAIN

The latest round began when a minister, who was in Kota Kinabalu for an official event, mentioned on social media how pleasant it was to go for a run under bright early-morning skies. As those who have travelled to East Malaysia doubtlessly known, sunrise in Sabah comes noticeably earlier than in the Peninsula, even though both regions share the same official time. The minister’s remark was innocuous enough, but it struck a chord.

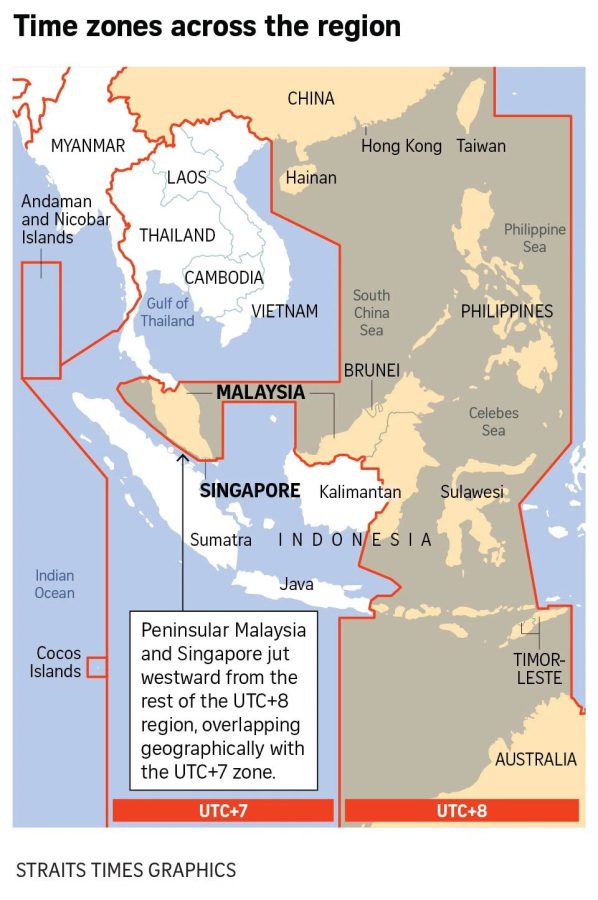

Morning light, many commenters argued, is exactly what Peninsular Malaysia lacks. On the Peninsula, sunrise hovers around 7am for much of the year. By comparison, Bangkok and Jakarta enjoy daylight well before 6am, despite lying along similar longitudes. Singapore, which shifted its clocks alongside Malaysia in 1982, faces the same relatively late sunrise time. (On the date of this article’s publication, KL’s official sunrise time was 7:01am, while Kota Kinabalu’s was 6:08am. Kuching, meanwhile, had a sunrise time of 6:24am.)

Compounding the issue, the near-equatorial position of Malaysia and Singapore precludes much of an extended dawn (or dusk), like that experienced in northern or southern latitudes. As the sun strikes the Earth’s surface much more directly near the equator, it’s still quite dark 15-20 minutes before sunrise. (During part of the year in Europe and North America, for example, a gradually lightening dawn goes on for well over an hour before the official sunrise time, and similarly, once the sun sets, people still enjoy a solid hour of residual daylight.)

For many people, especially early commuters and parents of schoolchildren, the “late” sunrise here is simply part of life. But others see it as an unnecessary mismatch between geography and social schedules – one that they argue affects everything from energy levels to sleep patterns.

THE HISTORICAL REASONING AND TODAY’S ARGUMENT

When the government moved the Peninsula to GMT+8, it framed the change as both practical and symbolic. Sabah and Sarawak were already on GMT+8, and unifying the national time meant smoother travel, easier coordination for businesses, and fewer complications for public institutions. Synchronizing the clocks also represented a strengthening of national cohesion just two decades after the formation of Malaysia.

Singapore followed the shift immediately, citing similar practical considerations. The region has remained aligned ever since.

Back then, the change was met with relatively little resistance. Today, however, the conversation is far more layered, influenced not just by convenience, but by public health discussions, digital communities, and comparisons across ASEAN.

One of the strongest modern arguments in favour of returning to GMT+7 centres on circadian rhythms. Advocates say that when the sun rises late, people spend their first waking hours in darkness, and that this misalignment may affect sleep quality, productivity, and metabolic health.

A circadian rhythm is the body’s internal 24-hour cycle, shaped mainly by exposure to natural light. Supporters of a rollback argue that earlier daylight could encourage better habits, including morning exercise and more consistent sleep schedules. Some Malaysians who have lived or worked in Sabah and Sarawak claim they felt healthier and more energized there, partly because their days began in daylight rather than darkness.

However, medical experts typically caution against oversimplifying the issue. Many are unconvinced that a one-hour difference would deliver significant benefits on its own. They point out that diet, sleep timing, activity levels, and meal patterns have a much larger influence on long-term health. Even in neighbouring countries with “better-aligned” time zones, lifestyle diseases remain a challenge.

In short, while daylight can play a role, switching time zones would not be a cure-all unless broader behavioural habits change as well.

WHY A CHANGE IS UNLIKELY

Despite the growing online chatter, the government has been consistent in saying that returning to GMT+7 is not on the table. Officials have noted that altering the national time would create economic ripple effects. Businesses, schools, public agencies, transport networks, and cross-border activities would all need adjustment.

Moreover, Malaysia has spent over 40 years operating on GMT+8. Reversing the shift now would require a significant logistical effort for a change that remains scientifically debated and politically divisive.

For many policymakers, the 1982 decision still stands as a sensible one: one country, one time zone.

If a change is unlikely, why does the discussion keep resurfacing? In part, it reflects shifting lifestyles. Many Malaysians work long hours, spend more time indoors, and eat later at night than in generations past. Those factors feed the sense that daily routines feel “off,” especially when mornings begin in darkness.

There is also a growing public interest in health, wellness, and sleep science. Social media discussions amplify these perspectives, bringing niche debates into mainstream view.

For others, the conversation touches on identity and regional pride. Sabahans and Sarawakians often enjoy brighter mornings, while some on the Peninsula feel their schedules are out of sync with nature. The comparison fuels a recurring desire to rethink how the country marks time.

For now, all of Malaysia’s clocks will continue ticking along on GMT+8. But the renewed attention — sparked by something as simple as a minister’s morning run — shows how a seemingly technical topic can tap into deeper questions about lifestyle, health, and national choices.

Time zones may be fixed on maps and other documents, but the way people experience time is far more personal. As long as early mornings remain dark on the Peninsula, and conversations about wellness continue to grow, the question of whether Malaysia is in the “right” time zone is unlikely to fade away.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The term GMT, or Greenwich Mean Time, has now largely been replaced by Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC. The former term was retained throughout this article for consistency with its historic context.

SOURCES: The Straits Times; The Star; archival Malaysian government records.