With all components of the BUDI95 subsidy rationalization now having been announced, and implementation starting this week, it’s easy to wonder what possible benefits it’s expected to yield for the country.

Okay, first a few disclaimers and caveats. First, and most importantly, this is an opinion piece, a simple sharing of my sometimes-scattered thoughts on this so-called rationalization exercise. Second, there may be future plans or ideas in play that have not been made public. I have no special insight into the government’s thinking, and they certainly did not consult me before putting this plan into motion. So take all this with a pinch of salt, because there may well be elements of which I am simply unaware. And third, I must stress that I very much like living in Malaysia, but as a long-term expat here, I tend to notice and question things more like a local than perhaps any new arrival would do.

That said, I really have to wonder what is even the point of all this fuel subsidy wrangling? Come along with me as I try to unpack the arithmetic, find some logic in the plan, and take the opportunity to rant and fume a little bit along the way.

GOOD ON PAPER, BUT IN PRACTICE…?

Let’s take it step by step. Initially, we were told that the RON95 subsidy reform was necessary because Malaysia was spending far too much subsidizing fuel at a time when the country’s revenues were lagging, something that really got accelerated during the pandemic years. (Of course, fuel consumption surely must have plunged dramatically in at least 2020 and 2021, as well.) I think I saw the figure RM81 billion a year being bandied about as the cost of cheap fuel, but in fact that was the price tag for all subsidies, of which fuel carried the highest cost. So the plan was to end blanket subsidies and impose targeted subsidies, theoretically ensuring only the low-income groups in Malaysia would benefit.

Well, that plan did not come to pass. As it turns out, Malaysia is not much different than other countries — including my own — in that it really has very little appetite for taxing the rich and powerful, particularly when elections are looming on the horizon. (Remember how quickly and quietly the much-touted high-value goods “luxury tax” went away?) So now, every Malaysian, regardless of income, will receive the subsidy. All that is needed is a MyKad and a valid driving licence. It does not matter if you are living in Bukit Tunku, earning RM40,000 a month, and driving a brand-new Mercedes S-class or if you are in a rural kampung scraping by on RM800 a month and relying on only an old 125cc motorbike to get around — if you are a Malaysian, you will get the fuel subsidy in full. The overall scheme has been branded as Manfaat Rakyat BUDI MADANI RON95, or BUDI95 for short.

Translation of “Manfaat Rakyat Budi Madani RON95”

- Manfaat = Benefit

- Rakyat = The people / citizens

- Budi = Virtue, goodwill, or kindness

- Madani = Civil, inclusive, or referring to the current “Madani” government slogan

- RON95 = The grade of subsidized petrol (95-octane)

Together, the phrase means “People’s Benefit Budi Madani RON95,” referring to the government’s subsidy programme for RON95 fuel under the Madani initiative.

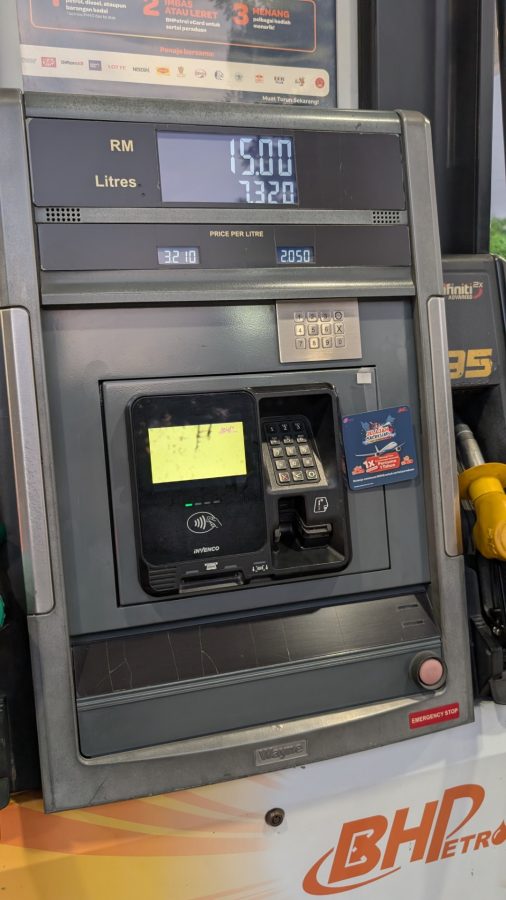

But wait, there’s more. Despite the urgent, desperate talk about reform to save Malaysia’s money, the government announced a while back that they would actually be increasing the subsidies. That’s right — from September 30, the benevolent government has increased the subsidy by an additional 6 sen per litre, driving the pump price down from RM2.05 to RM1.99 per litre. The announcement was greeted with a fair degree of mockery by locals on social media; it is, after all, a decidedly meagre reduction. And as some locals have noted, for the poorest Malaysians who have only a small motorbike and may use just 40 litres of petrol per month (if that much), this will save them a whopping RM2.40 per month.

To be fair, this announcement was made when it was still planned to extend the subsidies only to the B40 and possibly M40 groups, but now that the benefit will apply to all Malaysians, the government’s cost for providing cheap fuel will likely go up as long as they keep the subsidized price at the announced RM1.99 (unless the global price of crude oil drops).

THE ARITHMETIC

Let us do some basic arithmetic, purely as a thought exercise. We are told by the government that up to 18 million Malaysians will benefit from the BUDI95 subsidy scheme, though that figure has occasionally been as low as 16 million. We’ll use the latest and go with 18 million. Every Malaysian gets an allocation of 300 litres a month at the subsidized price, except for registered e-hailing drivers, whose monthly allowance is unlimited. For ease of calculation, we’ll just give 300 litres to everyone, as some will use more and many will use less.

So that is 300 litres times 18 million people, or 5.4 billion subsidized litres a month. We are told that the unsubsidized price is RM2.60, so the subsidy saves an eligible driver RM0.61 per litre. So the cost to the government? Just a bit under RM3.3 billion per month, or a little under RM40 billion per year.

Those are big numbers. If the government’s stated goal was fiscal prudence, this figure raises immediate questions about how well that objective is met by the policy on the table. We’ll see how it compares to the current scheme in the next section.

BUDI95 — Quick Numbers

- 18 million Malaysians eligible

- 300 litres per person per month (e-hailing drivers: unlimited)

- Subsidy per litre: RM0.61 (unsubsidized price RM2.60)

- Monthly subsidised litres: 5.4 billion

- Estimated monthly cost: ~RM3.3 billion

- Estimated annual cost: ~RM40 billion

Let’s continue the mathematics by bringing foreigners into the equation, that group that we were told is a big part of the reason Malaysia had to reform the fuel subsidies to begin with.

ARE FOREIGNERS REALLY AN ISSUE?

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has stated in public press conferences, without providing data to back it up, that merely excluding foreigners from the BUDI95 scheme will save the government RM8 billion (that’s billion, with a ‘b’) a year. That is almost impossible to reconcile with the government’s own numbers on foreigners in Malaysia.

(The “savings” numbers have since flip-flopped around dramatically – RM2.5 billion, RM3 billion, RM960 million. I think it’s probably safe to say nobody really knows what, if anything, will be saved until the program is up and running.)

But once again, we can work the numbers. Immigration figures show that not even 150,000 expatriate work visas are in play now, so let us generously assume that means 150,000 expats living in the country. Of course, not all of those expats drive, but we’ll play devil’s advocate and say they do. There are also about 2.5 million registered foreign/migrant workers in Malaysia as well, again by the government’s own reckoning. However, very few of those workers own private vehicles and drive in Malaysia. Migrant workers overwhelmingly rely on public transportation and walking.

So if we extend the 300 litres a month that the government says is a reasonable amount of fuel to each of the 150,000 resident expats, and multiply by that RM0.61 per litre, we arrive at RM27.45 million a month, or a little over RM329 million a year. That is certainly a lot of money, but it is not anywhere close to RM8 billion (or even RM1 billion, for that matter).

So where did that mystical RM8 billion figure come from that the prime minister claims Malaysia will save by excluding foreigners from the fuel subsidy scheme? Well, he didn’t say. (He also stated in 2023 that RM17 billion in fuel subsidies went to the T20 income group in Malaysia, making observers wonder exactly how that very specific figure was calculated, since nobody is required to produce tax returns or financial documents when filling up their car.)

The suggestion that subsidizing fuel for 18 million Malaysians would cost RM40 billion a year while subsidizing fuel for 150,000 expats — which is 1/120th the number of Malaysian drivers — would cost RM8 billion a year is mathematically preposterous on its face. If the tally for the claimed cost of subsidizing fuel for foreigners were extrapolated for the 18 million driving Malaysians, it would be RM960 billion a year, not RM40 billion.

Let us further compare the numbers to what is offered pre-BUDI — a RM0.55 per litre blanket subsidy. Using the 18 million driving Malaysians, plus 150,000 driving expats, times 300 litres per month, we arrive at a cost to the government of RM2.9948 billion per month. We will round it up to RM3 billion, or RM36 billion a year.

Under the new scheme, as we have already seen, the cost of subsidizing the fuel at the higher rate (RM0.61 per litre) for the same 18 million Malaysians, even when excluding foreigners from eligibility, is RM40 billion a year. By the government’s own figures, the subsidy rationalization will cost Malaysia more, not less.

Subsidy arithmetic at a glance

- 150,000 expats × 300 litres × RM0.61 = RM27.45 million per month (~RM329 million per year)

- Government’s claim: excluding foreigners saves RM8 billion annually

- If the RM8 billion figure were extrapolated, subsidies for Malaysians would hit RM960 billion annually

- Current blanket subsidy (RM0.55/litre): ~RM3 billion per month, or RM36 billion per year

- New scheme (RM0.61/litre): ~RM40 billion per year, even excluding foreigners

By the government’s own numbers, the subsidy “rationalization” raises costs instead of reducing them.

BUT WHAT ABOUT THE SMUGGLING?

Okay, but this arithmetic does not take into account “leakage” — the genuinely serious problem of millions of litres of subsidized fuel being smuggled, often across the border with Thailand, by organized syndicates. The presumed thinking is that by limiting the subsidy to 300 litres a month and tying the allocation to a person’s MyKad, those leakages will be curtailed.

And honestly, that reasoning is sensible in the abstract. Unless the government begins issuing chip-enabled ID cards to resident expats, it makes sense that foreigners would, by right, be excluded. However, the government could provide such cards. Expats are already issued an ID card by immigration — a relatively newly relaunched initiative that replaced the iPass card expats once received, though that was later discontinued. So while expats in Malaysia get government-issued ID cards, they do not have a chip. Adding that functionality would be straightforward though, and then working expats, who pay significant income taxes to Malaysia, could receive the same fuel subsidy benefit, or perhaps be exempt from the loathsome nightly tourism tax at local hotels. What a wonderful, welcoming message that would send.

Because of the massive problem with fuel smuggling, however, and because smuggling is commonly done with the combined efforts of locals and foreigners, including truck drivers and petrol station owners, tying the subsidy eligibility to the only chip card available now, the MyKad, makes sense on paper.

But if there is one thing I have learned after living in Malaysia for nearly two decades, it is this: crafty people will always find the loopholes. It will take incentivized Malaysians about five minutes to figure out how to exploit any weaknesses in the new scheme. Will BUDI95 effectively stop large-scale smuggling of petrol? That is an open question, and one I would not bet on without seeing strict enforcement, widespread and transparent auditing, and a robust digital tracking system.

OTHER SCENARIOS

I’m not the only person asking about the rationale behind all this. A number of op-eds and articles in local media (written by Malaysians, to my great appreciation) are posing similar questions, with some rightly asking why resident foreigners, especially those who pay taxes here, are being excluded when the government’s own arithmetic suggests the savings would be tiny.

In July, while defending excluding foreigners from the BUDI95 scheme, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim stated that, “Foreigners do not pay taxes like Malaysians.” Well, no, they don’t pay taxes like Malaysians at all — they actually pay far more! In truth, about 85% of working Malaysians pay no income tax whatsoever. Perhaps migrant workers don’t pay taxes, and maybe that’s who Anwar was referencing, but as previously noted, they don’t generally own private cars and drive in Malaysia, either.

Resident expats, however, most assuredly do pay taxes to the Malaysian government, and in rather copious amounts. They also open businesses here, bring in foreign investment, hire Malaysians, and contribute in many other ways. Much of the same can be said for resident MM2Hers, who will also now be excluded from the subsidy. It would have been far more accurate had the PM made the distinction in his comments.

Unfortunately, misinformation about this seems to persist. I saw a segment on the news just recently in which a Malaysian man was being asked about the BUDI95 scheme. He opined that it was good because “It benefits the citizens, not the foreigners,” and since the citizens are the taxpayers, they are the ones who should be getting the benefits from those taxes. Wouldn’t he have been surprised to know that 85% of his fellow working Malaysians do not, in fact, pay income taxes, and foreigners – at least resident expats – very much do pay taxes! (See video below, at 1:01)

A very real question persists, though: Will excluding foreign residents even be effective? Or will expats simply have Malaysian friends and family handle their fill-ups? For expats with Malaysian spouses, the local partner will likely do the pumping using their own MyKad. Will vendors be checking the identity of the purchaser? And what of Malaysians without driving licences — they will be automatically excluded by the rule that a MyKad and a valid driving licence are required. Will enforcement be equitable?

I have also seen threads on social media worrying about personal data being used to track where people bought petrol, how much, and when. Such “big brother” concerns are becoming more common in a hyperconnected and almost endless online world. The idea of government databases being used to monitor and track our daily lives is not an abstract fear anymore.

Another important point is how any gains are distributed. Once again, the poorest — often rural Malaysians, the very people the policy purports to help — will not see substantial benefit. A person in a kampung using only a few litres of petrol per week for a small motorbike will see limited savings. Conversely, a wealthy couple in Bukit Damansara, each driving a large imported car, will enjoy 600 litres of subsidized RON95 every month, saving their household about RM4,400 per year over the full RM2.60 per litre price. Targeted subsidies? To my eye, they now look a lot less targeted in practice.

There is the possibly significant fact that companies are now excluded from RON95 subsidies, too. However, it’s hard to quantify how meaningful this will be until some time has passed. For instance, many companies and fleets use diesel, not RON95. Additionally, as one local news story pointed out, drivers for companies can still use part of their own allocation to fill company vehicles, perhaps getting reimbursed at a rate per litre that’s more than RM1.99, but less than RM2.60, effectively giving them a small bonus.

Similarly, as reported by The Edge, enterprising Malaysians can easily “sell” their unused allocation. “For instance, a family with five eligible members, but who use motorbikes, would not need the 1,500 litres of subsidized petrol allocated to them,” the report states. “Conservatively, selling 1,000 litres to foreigners at even RM2.30 per litre can net the family a few hundred ringgit a month.”

Indeed, the law of unintended consequences will undoubtedly make itself known in the coming months. One thing seems fairly certain, though: Reports of wayward Singaporean motorists illegally filling up with subsidized RON95 in Malaysia will decline rather dramatically. However, I’m equally sure that they’ll cheerfully fill up (legally) at the RM2.60 rate, a figure still less than a third of what they pay on the island.

AN UNCERTAIN PATH FORWARD

Now admittedly, for me personally, the change will not deliver a major blow to my bank account — I do not use anywhere near 300 litres of petrol a month. My estimate is closer to about 100 or 120 litres, so the extra cost is roughly RM70 a month. That assumes none of my local friends fills up on my behalf, which several have already offered to do. RM70 is not nothing, but it is not a crippling figure, either. Yet the principle of the matter is what really stings. After 17 years here, this seems to be another in a series of recent reminders that I am increasingly treated as an undesirable outsider — soaring work visa costs, higher taxes, tourist tax despite not being a tourist, inflated attraction prices compared to locals, and now exclusion from this subsidy. I’ve even seen recent articles saying there’s a possible plan to put QR codes on subsidized cooking oil to ensure only Malaysians receive that benefit. Honestly, it’s hard to take any of this as a particularly welcoming gesture by the country I’ve called home for roughly half of my adult life, which is a real shame.

It remains to be seen how much difference the new RON95 subsidy plan will make for Malaysia. I still believe a simpler approach could have worked better: incrementally increase the price by 5 or 10 sen every few months until it reached a level such as RM2.30 or RM2.35. The fuel would remain partly subsidized, the government would save significant sums, and there would be no need for a costly and convoluted implementation and enforcement mechanism that does not seem to be truly targeted.

As it stands, BUDI95 risks becoming an expensive, administratively heavy exercise that fails to actually solve the core problem. Or, on the other hand, it could end up being a big success. From what I’ve read in local media and heard from Malaysians on the ground, though, it frankly looks a lot less like rationalization (and nothing at all like targeted subsidies) than political compromise ahead of impending elections. We will have to wait and see whether it does anything productive beyond making for a potentially messy chapter in public policy.