Faith, commerce, and bud get travel. If that sounds like a rather curious trinity, consider the three streets I explored in Kuala Lumpur – each focusing to some degree on one of those subjects.(Whether by accident or design is a different story, however.)

With a camera, a trusted pair of shoes, and a vigilant spirit – it is the inner city, after all – I found each of these three streets (one more a collection of streets than a single thoroughfare) to be remarkable and enjoyable to explore, each in a different way.

Jalan Gereja

This is possibly one of the shortest streets in Kuala Lumpur but a special one, especially for its Roman Catholic citizens and visitors, as it leads to the Church of St. John the Evangelist, Kuala Lumpur’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, and also the seat of the its Archbishop. Interestingly, the cathedral is not actually on Church Street but set a little above it on Jalan Bukit Nanas.

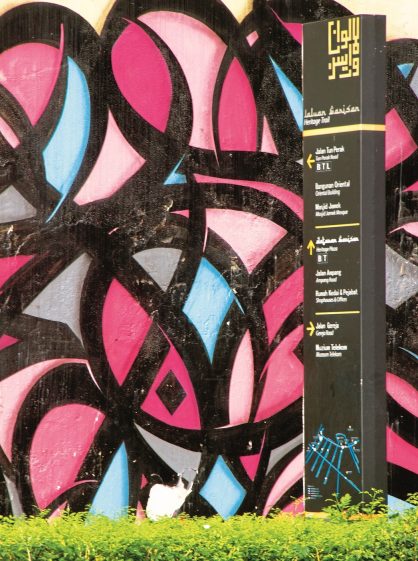

Jalan Gereja extends for 100 metres or so from Jalan Raja Chulan, near the Muzium Telekom and the Maybank Headquarters, to where it seemingly morphs into Jalan Ampang at the Leboh Ampang intersection. However, Church Street provides access to the cathedral and the immediate area,which is an interesting enclave of colonial buildings and Indian curry houses that becomes a hive of activity on Sunday morning as parishioners attend morning mass.

Bukit Nanas (Pineapple Hill) is a fascinating part of Kuala Lumpur, with the southeastern side of the small hill being a forest reserve called Hutan Lipur Bukit Nanas, which supports one of the last remaining patches of primary forest in or around Kuala Lumpur.

On the Chinatown side, the original wooden St. John’s Church was established here by the Reverend Father Charles Hector Letessier on Bukit Nanas in 1883. The original church was constructed with the financial assistance of a wealthy towkay and Chinese Malaysian Catholic by the name of Goh Ah Ngee who hailed from Kajang. The current cathedral was constructed in 1954, with its consecration not taking place until 1962, when it was also elevated to the status of a cathedral.

There was once another place of religious worship along the same street. The Kuala Lumpur Episcopal Tamil Church built in 1897 was located at the intersection with Jalan Malacca.

The carnival-like setting outside the cathedral doesn’t appear to distract from the serious religious matters conducted inside the building. While hymns are enthusiastically sung inside, candles are lit in the grounds and blessings are sought in the cathedral’s grounds, the streets surrounding the cathedral become a colourful bazaar in the mornings.

Many Christian domestic helpers from the Philippines and other parts of the region have Sundays off, with this day of rest normally starting with a church service and then the opportunity to socialise and eat with their friends afterwards. Food and beverage stalls line the street and offer visitors an opportunity for all to enjoy some home-cooked dishes from other parts of the region at great value-for-money prices.

Education shares space with religion here, too, as two schools are situated along Jalan Bukit Nanas; SMK St. John’s Kuala Lumpur (or St. John’s Institution) and Sekolah Menangah Kebangsaan Convent (SMK Convent Bukit Nanas) at the cul-de-sac at the southern end of the road.

The architecture of the former is the one that captures the attention of passers-by for its striking red brick and contrasting white colours. St. John’s was established by the Roman Catholic Mission in 1904 as a school for young boys. It is named after Jean-Bapiste de la Salle, the founder of the De La Salle Christian Brothers Order. Historical records indicate that the original wooden building housed 18 male students with Brother Julian Francis being the Brother Director (Headmaster).

The building that now stands on the site dates back to 1907, with its architecture exhibiting Grecian Spanish influences. At the time it was erected, it was the most substantial educational institution in the country. Today, apart from a few extensions, the building remains much the same as when it was first built. One thing that has changed is that the school is now co-educational in the senior years. However, it remains, as it always has been, multi-ethnic and multireligious. A glance through past student rolls indicates that sultans, politicians (including the current Prime Minister), and leading business people are listed as ex-students.

Market Square

Kuala Lumpur’s beginning is hardly a glorious one, and even its name – which meansmuddy estuary – lacks the glamour ofmany other world capitals.

Its humble beginning dates back to the 1850s when tin was discovered at the confluence of the Klang and Lumpur (the latter is now called Gombak) Rivers at the location now dominated by the ornately-decorated Masjid Jamek (Jamek Mosque). This location was probably chosen by default, too, as big boats couldn’t proceed any further upstreamfromthis river junction and were forced to offload their cargo on the riverbank.

Here, a rough and ready mining camp was established, and one can only assume it lacked any airs or graces and that it was a wild frontier certainly not for the faint-hearted. History records that the early days were plagued with disease, floods, and fires. Various factions muscled in on the tin production, and disputes were

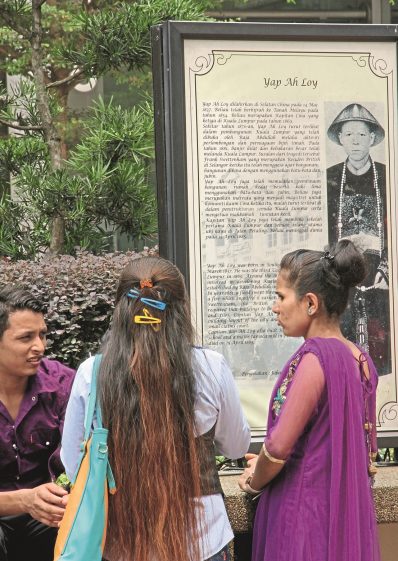

common. These culminated in the Selangor CivilWar (1870-1873) which didn’t help harmonious relations, but life became a little more ordered when a leading player, Kapitan Cina (headman) Yap Ah Loy, asserted his dominance.

The first markets had been established where the boats offloaded their  goods from their journey from Port Klang and the outside world. Naturally, this became the economic hub of the new settlement, and historians suggest it would have been the first part of the burgeoning town to be rebuilt after the civil war.

goods from their journey from Port Klang and the outside world. Naturally, this became the economic hub of the new settlement, and historians suggest it would have been the first part of the burgeoning town to be rebuilt after the civil war.

By this stage, Yap Ah Loy had become the most powerful man in the community and his house on Market Street was close to all the action. He was born in Guangdong in 1837 and moved to Malaysia in 1854 to seek his fortune. Like many, he first headed to Malacca and eventually became a tin miner and petty trader.

Known as the founding father of Kuala Lumpur, he also owned the land and market where he operated a piggery, abattoir, and workshop. The area in front of Yap Ah Loy’s house became known as Market Square (Medan Pasar) as it was the town centre. Today, there is an information sign in the middle of Market Square detailing the contribution he set in place for the growing settlement and what was to become the capital in 1880.

Over time, he accumulated a small fortune and saw benefit in law and order being established, if only to protect his property. He successfully liaised with the local Malays and also the British when they intervened in 1874. Yap Ah Loy put in place a town administration and a small force to maintain law and order. After a disastrous fire in 1881, the then-British Resident Frank Swettenham mandated that buildings were to be constructed from brick and tiles and thatching (atap) roofing was subsequently banned.

Yap Ah Loy mobilised his forces and fortune to establish a brick-making factory in, not surprisingly, what is today called Brickfields. Many fine brick and tile buildings of this early era still stand in Market Square.

Following Swettenham’s mandate, it was possible to construct more substantial and higher buildings from brick and mortar with the architectural inspiration mostly coming from southern China. Later, moreWestern elements were introduced and today, Market Square is quite eclectic in its architectural style with typical Chinese shophouses of two and three storeys dominating. These were initially built in rows (like terraces) with common walls between each one. These were typically long and narrow mostly to reduce rates paid, which were calculated on the width of the street frontage.

with the architectural inspiration mostly coming from southern China. Later, moreWestern elements were introduced and today, Market Square is quite eclectic in its architectural style with typical Chinese shophouses of two and three storeys dominating. These were initially built in rows (like terraces) with common walls between each one. These were typically long and narrow mostly to reduce rates paid, which were calculated on the width of the street frontage.

The bottom floor with street frontage was a retail outlet while the first and second floors were where the family lived (usually an extended family). Once the new building code was enforced, the first floor mostly extended over the ground floor to create a covered area which became known as the ‘five-foot’ walkway (kaki lima). This provided shelter from the sun and rain for those walking along the street as well as an area where retailers could extend their retail space.

Historians refer to the architectural styles as Utilitarian (1880s – 1890s), Neo-classical (1900s – 1930s), and Art Deco (1930s – 1940s). Examples of all can still be seen in Market Square with the building originally called Sin Seng Nam Restaurant (now with the name Kafe Old Market Square and looking like it no longer operates) is one of the most interesting buildings with its white façade plus black and yellow shuttered windows. It was designed by a Hong Kong-born architect by the name of A.K. Moosdeen who also designed the well-known PAM Building (the home of the Malaysian Institute of Architects).

It was originally called the Red House because its bricks were initially unpainted. The building has fine Dutch gables which wouldn’t make it look out of place along an Amsterdam canal. Art Deco architecture is seen in the clock tower in the middle of the pedestrian square. This was erected in 1937 to commemorate the coronation of King George VI and includes classic sunburst motifs so typical of Art Deco. The square is bounded by Jalan Pasar Besar Jalan Silang on the eastern bank of the Klang River. Just beyond it is Central Market.

Market Square has the dimensions of a football field and being a pedestrian-only area, it is very popular as a meeting place, especially on Sundays when a sizeable number of Malaysia’s foreign workers gather and meet here. It’s a vibrant and colourful scene and while male dominated, it’s not entirely free of females. There is a convivial atmosphere, as most of these workers are very happy to have the day off from their working week. Many of the banks remain open so that these workers can send their wages back to their families in Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh, and other neighbouring countries.

Market Square is best accessed by public transport from the Masjid Jamek LRT Station which is a five-minute walk away.

Tengkat Tong Shin

Though popular with visitors and backpackers, Tengkat Tong Shin flies largely under the radar of locals in Kuala Lumpur. As it is situated in the centre of Kuala Lumpur it is difficult to suggest that Tengkat Tong Shin is a truly hidden venue, but it is certainly one of those little streets that you generally don’t just happen to find yourself in; there needs to be a purpose to be here.

For me, there is a reason to be on this street several times a year as it is the home to Kuala Lumpur’s best and most consistent Vietnamese restaurant but more on that later. It’s my guess that more visitors to Malaysia, especially budget travellers, know of Tengkat Tong Shin than the local residents as it is home to several well-regarded backpacker haunts and is a stop on KL’s generally don’t just happen to find yourself in; there needs to be a purpose to be here.

For me, there is a reason to be on this street several times a year as it is the home to Kuala Lumpur’s best and most consistent Vietnamese restaurant but more on that later. It’s my guess that more visitors to Malaysia, especially budget travellers, know of Tengkat Tong Shin than the local residents as it is home to several well-regarded backpacker haunts and is a stop on KL’s convenient Hop-on, Hop-off bus (hoponhopoff.com).

The history of the area is also confusing, but generally it can be accepted that Tengkat Tong Shin is named after the hospital of a similar spelling, though the jury is still out on who established what was once a hospice. There is agreement that a traditional Chinese dispensary was established in the city on Jalan Sultan (in Chinatown) in 1881. However, there is conjecture as to whether the original institution called Pooi Shin Thong was established by Kapitan Cina or Yap Kwan Seng. Private money was used in its opening, and in 1894, the hospital was relocated to its current site and renamed Tung Shin Hospital.

The current hospital of 250 beds is located close to Tengkat Tong Shin and is still known for its traditional Chinese medicine. History suggests that Tengkat Tong Shin became an upmarket lane and home to wealthy Chinese with some rather smart terrace houses having been erected here. Modern Malaysian architecture hides much of this, but those who stroll along here can get an impression of what it may have once looked like behind the veneer of mirrored glass and aluminium cladding.

Its residential status declined after 1969, partly because more desirable addresses opened up in the expanding suburbs. The lane became slightly edgy as many inner city areas around the world can become but about a decade or so ago, changes to rental control freed up some of these places and now they are more commercial than residential in intent.

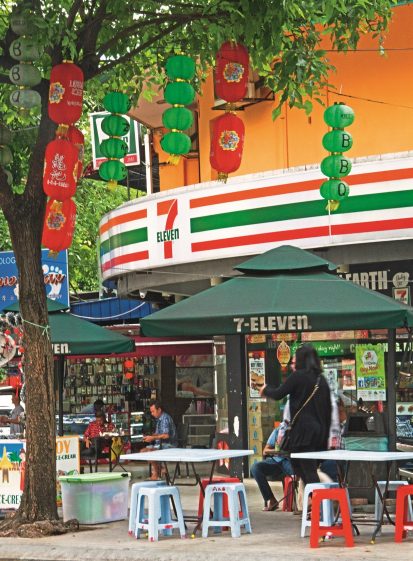

As far as a stroll down Tengkat Tong Shin goes, the lane can best be described as mixed use with a couple of substantive hotels, backpacker guesthouses, numerous spa and reflexology centres, hawker stalls, restaurants, bars, and shops.While definitely not the most glamorous part of the city, it has lots of character, with the small detail more of interest here rather than any iconic structure.

Food is usually a great motivator to acquire an interest in a street in KL, and while most of the offerings along Tengkat Tong Shin are local, there is a mini buffet of offerings to make it worthwhile to dine here. As it is parallel and just metres from KL’s favourite food street of Jalan Alor, it is perhaps a little surprising that there hasn’t  been more of a spillover here.

been more of a spillover here.

Tengkat Tong Shin is much more subdued and more a destination where locals residing along the lane dine. Some places only open from 6pm to 4am to give an indication that they cater to a hungry crowd of night owls. Cheap eating reigns supreme here with stalls and hawker centres dominating (the largest being SK Corner which does a fine tandoori chicken among a selection of other popular dishes). In addition to Chinese, Indian mamak and Malay stalls and restaurants, visitors can dine on Mongolian, Nepali, Pakistani, and Vietnamese food.

It is the latter, served at Sao Nam restaurant, that regularly lures me to the area. It’s been around a decade or so and the food is excellent and the wines are reasonably priced and international in their orientation. The restaurant is popular with its loyal fans and there’s always a constant flow of tourists guided by the restaurant’s favourable reviews.

A version of this article was originally published in The Expat magazine (August 2017) which is available online or in print via a free subscription.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "