For better or worse, many people methodically follow Malaysia’s daily Covid numbers, but a deeper dive into the data reveals that not all is as it seems.

We’ve written before that effective, accurate, and timely communication during a pandemic is both critically important and incredibly difficult. From shifting realities such as the approval of a vaccine or the emergence of new variants to – unfortunately – competing political agendas, governments around the world have at times struggled to maintain a coherent and meaningful script with regards to Covid-19.

Malaysia is no different, of course, and many of us check the new statistics on a daily or near-daily basis, poring over the data and using these numbers to form our opinion about “how things are going.”

But a new and welcome transparency in the quality and depth of data being made publicly available reveals that, when it comes to Malaysia’s ongoing battle with Covid, perhaps what we may have believed to be the case has often been shaped by poorly or incompletely reported numbers.

NEW DAILY CASES

This reported metric has long been the easiest to take with a pinch of salt, purely because it’s an easy number to manipulate – not in a nefarious or sneaky way, mind you, but merely by increased or decreased testing.

Simply put, if you’re testing more, particularly in an area of known contagion, you’re unavoidably going to pick up more cases. And to a large extent, that’s what’s been behind Malaysia’s recent surge of daily new cases: a lot more testing.

The only way to consistently achieve meaningful, specific data on this point is to test a lot and to test at about the same rate for a given population over time. This is, understandably, remarkably difficult to do, particularly because as you test, you inherently remove people from the testing pool. (For example, if you test 2,000 people out of a population of 15,000 on one day, the next day, you would only have 13,000 available to test.) This basic mathematical fact means you can’t realistically expect to test at the same rate over time.

Bottom line: Though it’s not a completely useless number, and can broadly be used to determine whether a pandemic is easing, spreading methodically, or exploding completely out of control, trying to tether any specific truth about the pandemic to the daily new cases is often a fool’s errand.

DAILY DEATHS

August 2021 was Covid’s deadliest month in Malaysia, establishing a benchmark for fatalities that we certainly hope will never be equalled. The reported death toll in August was 7,390. However, the actual number of deaths was higher – 7,630 – and that variance brings us to our next point.

For a long time, even those who largely discounted the daily new cases looked to daily deaths as a more reliable metric of the pandemic’s ebb and flow in Malaysia. As it turns out, this may have been an even less useful approach, simply because the number of deaths reported virtually never corresponds to the actual number of deaths on any given day, and as a more careful look reveals, is often not even close.

Part of this is down to the nature of such reports. According to the Ministry of Health, “Reporting of deaths is backdated, particularly to include deaths where time was needed to ascertain the cause of death. Therefore, trends should be observed from the series based on date of death (actual deaths).”

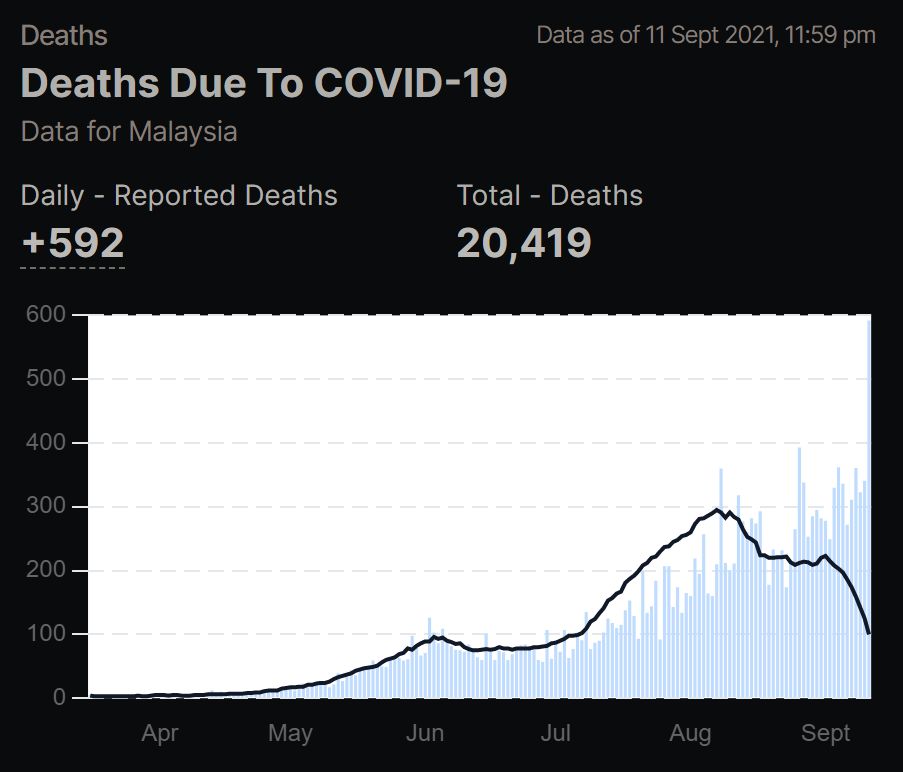

The discrepancy isn’t insignificant. In just one very recent example, on September 11, the number of reported deaths was 592, a record high by far. But when looking more carefully, that number included a lot of backlog. The actual number of deaths on September 11 was 100.

This isn’t an isolated instance, either. In fact, when analysing the data from every day since July 10, there isn’t one single day where the number of reported deaths corresponds to the actual number of deaths. There are just a handful of days where it’s off by a single digit. Many days have a double-digit discrepancy, and 18 days (out of 64) have a triple-digit margin of error.

Indeed, of the 64 days between July 10 and September 11, the discrepancy between reported and actual deaths is in double or triple digits on 59 of them, and the average daily discrepancy is 77.9.

The highest degree of variance was reached on August 11, when there was a discrepancy of 2,261 deaths between the reported and actual numbers.

You can appreciate how mangling a statistic as important as daily deaths during a pandemic can lead to incorrect assumptions, unnecessary anxiety, and a general sense of confusion and even distrust. In the graph below, looking at the blue bars (reported deaths) causes a true sense of despair, while looking at the black line (actual deaths) shows a very different reality: Progress is being made. Deaths are going down.

When looking at the Covid data from July 10 to August 9, the discrepancy is startling: 4,781 deaths were reported, while the actual number of deaths numbered 6,879, an under-reporting of 2,098 deaths. (Glancing at the chart above, anytime you see white space between the blue bars and the black line, that’s an under-report; the more white space, the bigger the discrepancy.) Conversely, anytime a blue bar extends above the black line, that represents some clearing of the backlog.

Only after the government “changed” on August 21, with Khairy Jamaluddin put in charge of the Ministry of Health, did the backlog begin getting seriously addressed. By the weekend before his appointment, the backlog had ballooned to 2,113 deaths in excess of what had been officially reported. With a cumulative death toll at that time of about 13,500, having a discrepancy of over 2,100 was troubling, to say the least.

And so, beginning around August 24 or 25, the backlog began getting cleared in earnest. Therefore, from August 25, every daily report of death has included, on average, over 134 “backlogged” deaths. As of now, the enormous backlog of deaths has been fully cleared.

The decision to make these corrections public, and also to vastly increase the quality and transparency of the data being released each day can only be applauded.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly for those of us trying to assess the status of the pandemic in Malaysia, since September 1, when 223 actual deaths were logged, the daily actual death toll has decreased every day.

On September 5, the actual daily death toll fell below 200 for the first time since July 21.

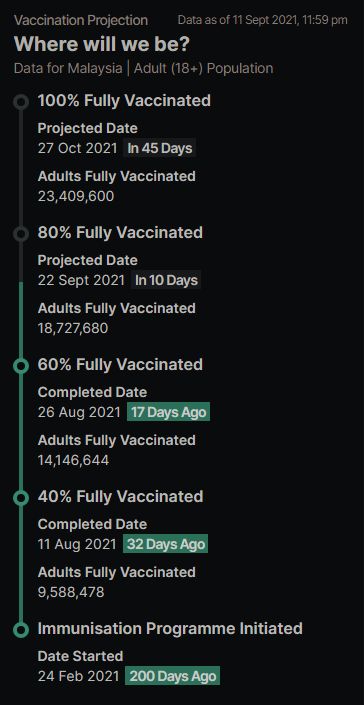

VACCINATIONS

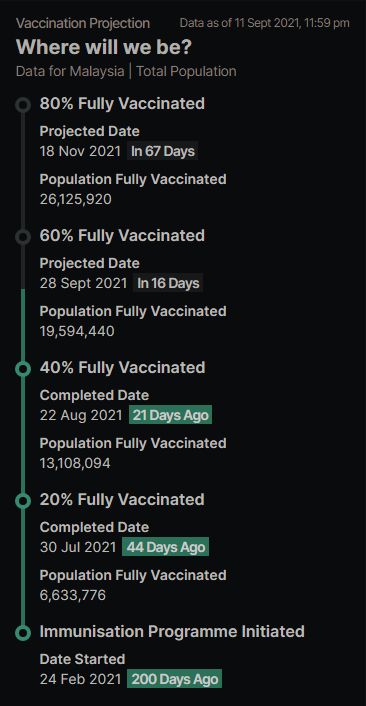

After an initial stumble, Malaysia’s robust vaccination effort is perhaps the one component of the pandemic response which has drawn plenty of praise.

As of September 11, about 52% of the population, comprising over 17 million individuals, have been fully vaccinated, with an additional 13% having received their first dose. About 2.7 million who have registered are still awaiting their first jab.

At first glance, the most unsettling statistic is that over 26% of the population – nearly 8.7 million people – have not yet registered for immunisation at all. A glance at this number might lead one to think that this shortfall will need to be vigorously addressed if Malaysia is to have any hope of reaching its target of 80% vaccination nationwide.

However, once again, looking at the numbers more closely and critically reveals a different truth. The strong majority of those who haven’t registered are those who simply cannot register on account of their age. When factoring that in, the number of adults (18+) in Malaysia who haven’t registered plummets to just 1.6 million. This will all need to be adjusted as and when Malaysia approves the vaccine for adolescents (12- to 17-year-olds), but for now, the outlook for Malaysia’s vaccination progress appears to be a positive one.

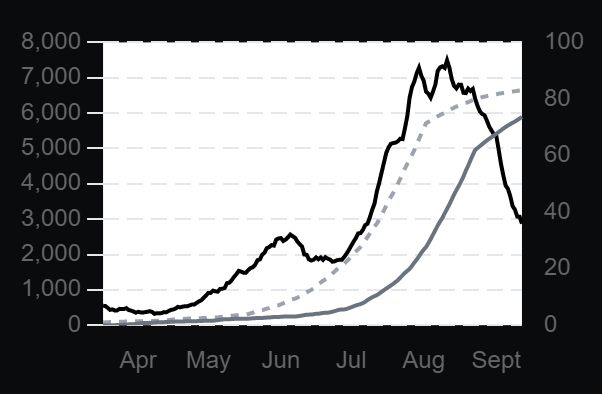

What’s particularly encouraging is seeing more specific, granular data supporting the long-held hope that cases and deaths would drop once vaccination coverage reached a certain threshold.

Looking at the graph for Selangor, which was for weeks the hardest-hit by the virus, you can see that new cases (solid black line) dropped precipitously as fully vaccinated rates passed 50% (solid grey line). The dotted line represents partial vaccination rates.

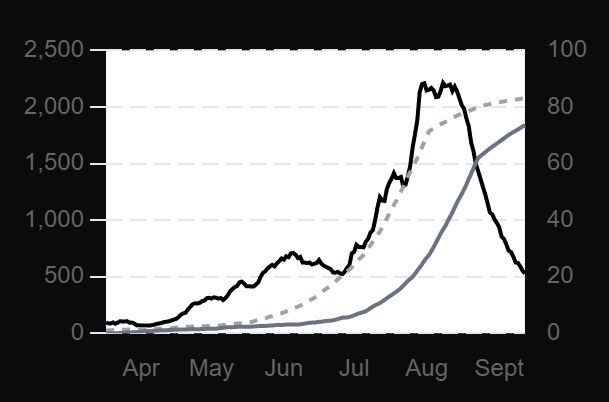

The data sets from Kuala Lumpur paint a very similar picture:

Moreover, hospitalisations and severe cases have also decreased steeply with the corresponding rise in the vaccination rates. Looking at Klang Valley as a whole, hospitalisations peaked around August 10-11, with over 6,100 in the region admitted to area hospitals for Covid symptoms. At that time, about 39% of the region’s population was fully vaccinated. Now, one month later, 73% of the people in Klang Valley are fully vaccinated and hospital cases have plummeted to 2,464. It’s still fairly high, but it’s considerably less than half of what it was a month ago and continues to drop.

For more serious cases requiring intensive care, a similar track has emerged. On August 10, there were close to 600 ICU cases reported in Klang Valley. A month later, that figure had dropped to 383. For those patients requiring ventilators, the story is much the same. On August 10, there were 427 patients on ventilators in the region; a month later, that number has been slashed nearly in half, with 224 now being ventilated.

The continued emergence of different strains of the virus, coupled with significant numbers of people who either cannot or will not get vaccinated, means that “herd immunity” is most likely not something we will be able to achieve with this virus. According to many virologists and immunologists, we should move away from thoughts of population-wide immunity and must now make a shift in our shared thinking and work instead towards establishing a new normalcy.

As we work our way through September into October, the coronavirus is expected to reach ‘endemic’ status in Malaysia, which according to authorities here, means that we will indeed change our approach from one focused on containment and mitigation to one focused on minimising death and severe illness, but otherwise learning to live with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its assorted variants.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "