Looking into your family’s genealogy is a great way to learn more about your heritage – and to discover stories all but forgotten.

This article contributed by Katrina Ling

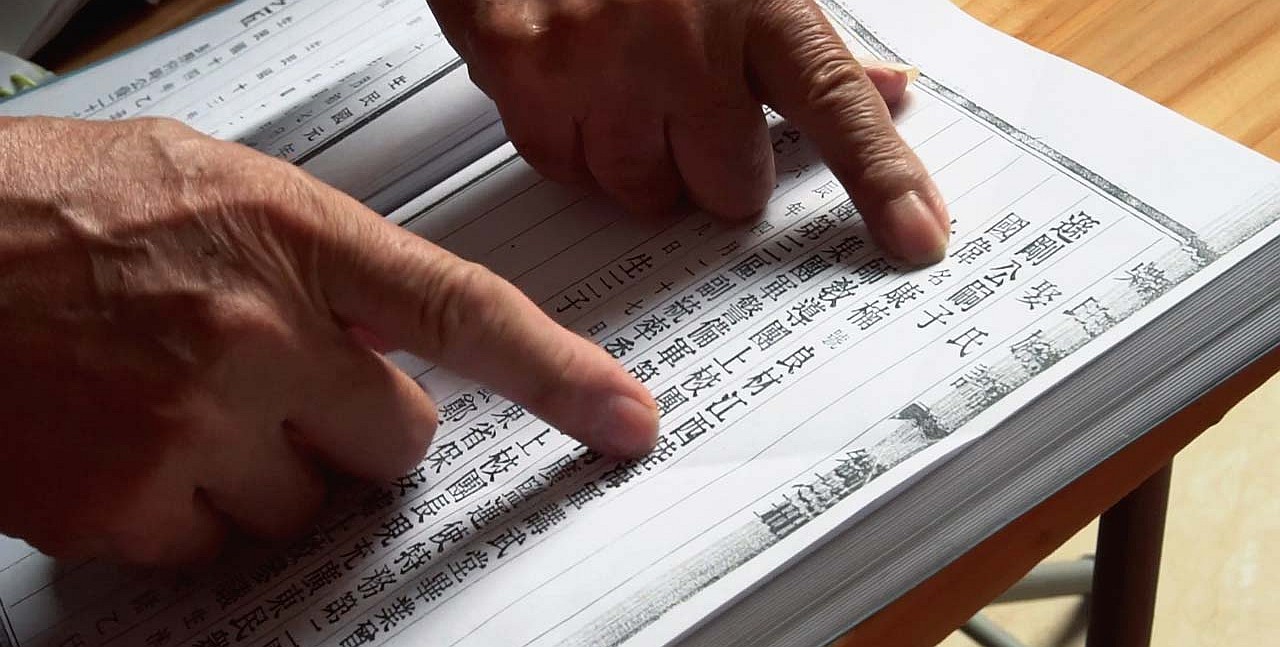

Of the few memories that remain from my childhood visits to Sitiawan for Chinese New Year, I distinctly recall having to attend a large gathering of people who shared my surname. Everyone in the cramped upstairs of a shophouse – definitely numbering more than 50 people – were fellow Lings. The only food served that day was economy bihun on paper plates, accompanied by a choice of beverages: chrysanthemum or wintermelon tea in cartons. At the front of the room, large banners bearing the 林 (lín) character were strung up. My family scavenged for flimsy plastic seats as we turned our attention toward a panel of older Uncle Lings, speaking in the Foochow dialect I never learned.

It didn’t occur to me at the time I was at a family reunion, not a convention of people who happened to have the same last name. Later on, there was a simple white booklet distributed to everybody. Its first page contained a black-and-white family portrait, in which one of the children turned out to be my grandfather.

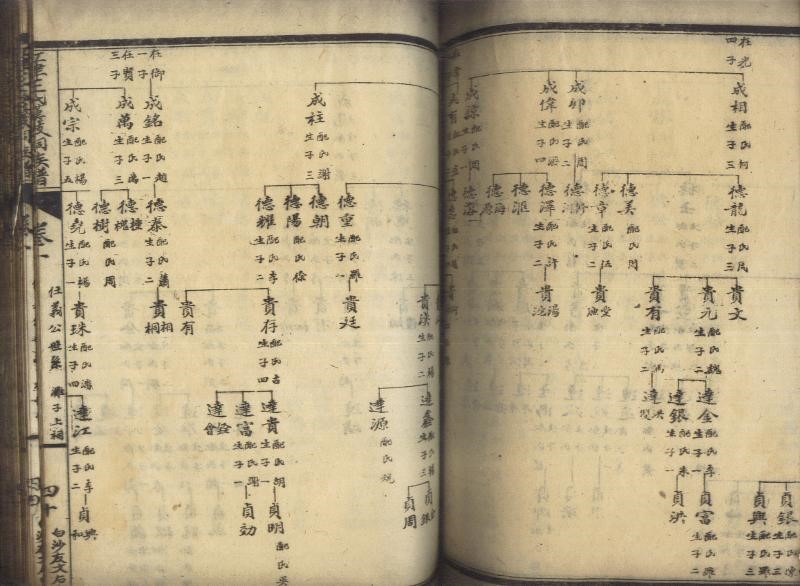

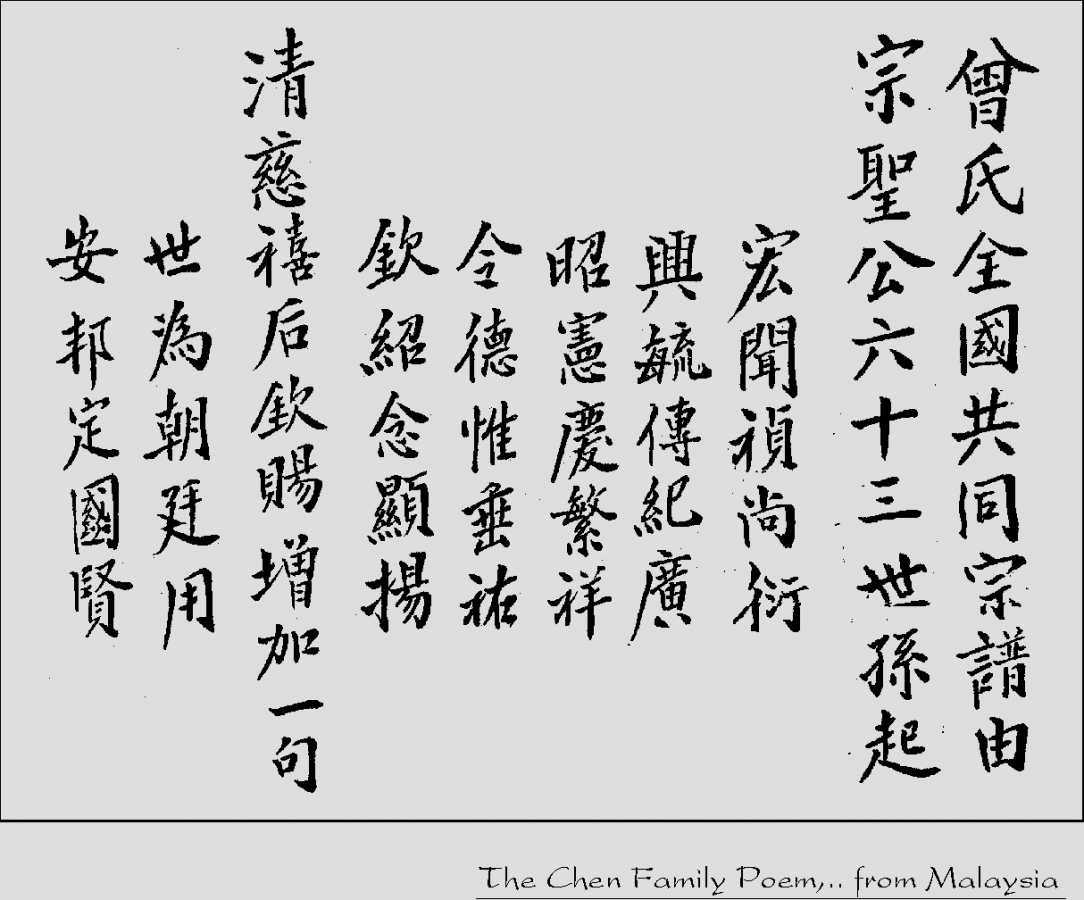

The next page was even more interesting. It was a name guide. In Chinese culture, the traditional structure of names is constituted by three characters. The first is the surname; the second, the generational marker; and the last was the individual’s unique name, or better known as style name. The guide was showing the intended names for every generation and style, each of which went through a sequence of 22 characters. This meant that the Chinese names of everyone born to this family had been determined and catalogued for them – for as long as the lineage lasted.

Beyond this, the rest of the booklet was a comprehensive log of every person in the family tree. My grand-uncles, grand-aunts, first cousins, second cousins once removed, on and on it went. You could tell it was purely for record; the only information listed for was the person’s name and birthday. I remember feeling excited seeing mine among many unfamiliar ones.

THE HISTORY OF CHINESE GENEALOGY BOOKS

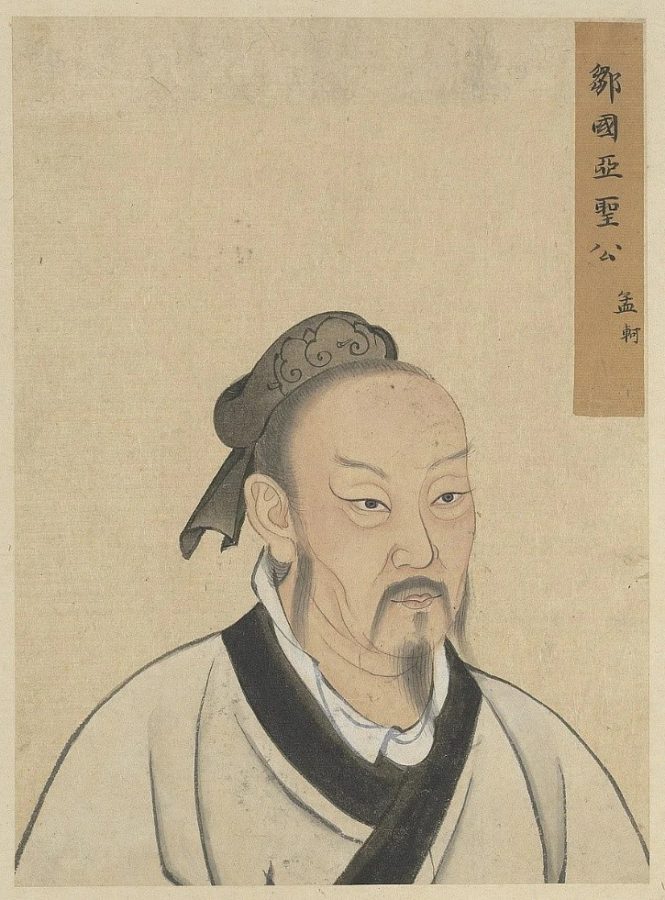

This practice of having a comprehensive family booklet – as I discovered only recently – was not a custom only to the Lings, but to many ancient Chinese families, with some stretching as far back as a millennium ago. Nowadays, if you want to trace your lineage, you typically begin with yourself and work your way back. You find your parents, and then their parents, and so on. But the old Chinese way was to work from the beginning – the root of the family tree; the common ancestor that ‘started it all.’ Some families were so meticulous with tracking their genealogy, they’d been doing it long before writing was even invented. The most notable ancestries, namely those of Confucius or Mencius, still exist today.

Chinese genealogy books, also known as a zupu (族谱), originate from both commonfolk and ruling dynasties, but both were largely for the same reason: ancestral worship. The sacrosanct filiality that is stereotypical to Chinese culture is never backgrounded in all its aspects. The dead are perceived to have divine powers, and so it would, of course, be rather rude if you didn’t know the person from whom you were requesting good fortune or to whom you were wishing peace.

Historically, there was another advantage to recording genealogy that gave the zupu its significance in Chinese culture. Once families started turning into entire villages, people had to find ways to keep track of one another. When it came to property ownership, for example, they needed to know who else in the family was in its possession. The zupu – much like a corporate hierarchy imprinted on an overcrowded clique – was for determining who had value in your life. It had the power to propagate social roles even within the family, because it specified how everyone was connected to someone else. Evidently, the sequence of naming styles in these books reflect the idea that one’s identity is never remote, but forever relative (no pun intended) to their vast kin.

AN ORIGIN STORY FOR THE DIASPORA

Unfortunately, many of China’s genealogy books were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and Sino-Japanese war. For those emigrating from China, there was suddenly no record of the life they left behind to take along. And so, naturally, many families revived their genealogy books. The zupu returned with even more preciousness to the ever-increasing Chinese diaspora, such as the Asian-Americans and Chinese settlers in Malaya during the early 20th century.

Commonly added to Chinese genealogy books all this while were stories of important events occurring within the family. With the modern zupu focused on migration from their homeland, these stories became doubly valuable to Chinese expats. Having a name wasn’t enough. There had to be an account of the kind of life they lived in China or how they had made it to their new country. It was primarily a retelling of family history, tales shared so their descendants would remember the culture no matter where they were – and appreciate their ancestors’ sacrifices. In actuality, these stories didn’t have to be very elaborate.

My own family booklet more or less summarized my great-grandfather’s journey from Fuzhou, southern China, to the rubber tree forests of Perak. More experienced and passionate clans, on the other hand, could have tales so extraordinary they bordered on legendary. A result of exaggeration, of course, partly because people had to show they knew more than memory served, but it also meant to make a powerful name for the family. It was about creating a heritage of greatness.

A GENEALOGICAL JOURNEY

Perhaps this is why many are now interested in discovering where they came from. And this applies to virtually anybody in the world, not just the Chinese. Today, genealogy can be traced online via websites like Ancestry.com, FamilySearch, or even DNA test kits that break down your ethnic roots. People appear to be in search of some identity that is inherent within them, an identity that has existed for thousands of years. What’s more inherent than that, however, is the human desire for belonging, and there is no one closer nor stronger than family.

Of course, Chinese tradition hasn’t been the only one to recognise this. The zupu – in both function and system – has its Korean equivalent, the jokbo. And in the far west, Icelanders have traced their ancestry to a point where their population can be interconnected. The Íslendingabók, or Book of Icelanders, was created sometime in the 1980s and published online in 2003.

The zupu’s intimate quality is a confluence of its great value as a lost piece of history and exclusivity to a family. It’s an heirloom that explains its own origins. For the Malaysian-Chinese of today, it spells out our significance as a new and fresh chapter of Malaysian nationals in the clan. Those dozens of faces I skimmed through in that plain white Ling booklet told a tale of growth, a testament to my great-grandparents’ sacrifice. There is much to appreciate about the lives our forefathers lived, all to culminate in who and where we are today. After all, our heritage, our family, our very existence does not come from nothing.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "