Malaysia’s planned move to scrap RON95 petrol subsidies may slash billions off the national deficit – yet the burden will fall hardest on hardworking vendors, commuter drivers, and long-haul workers. Meanwhile, the scapegoating of foreign residents is built on thin evidence, and simpler solutions could reduce the political fallout.

For decades, Malaysians have been described – only half-jokingly – as being addicted to cheap petrol. At RM2.05 per litre for RON95 currently, heavily subsidized fuel has shaped everything in the country from commuting patterns to consumer expectations, reinforcing the notion that affordable petrol is almost a birthright, not a benefit.

In recent months, the public has been inundated with talk of reform: use of the MyKad for fuel purchases, biometric ID checks at petrol stations, targeted fuel subsidies via e-wallets, cash aid for the B40 group, and even geofencing to prevent cross-border abuse. Each proposal seems more complicated than the last, yet none have inspired broad public confidence. At its core, the issue is wrapped in layers of political risk and bureaucratic overengineering – and it’s worth asking whether such an elaborate overhaul is even necessary.

Yes, subsidy reform is a conversation worth having, and broadly speaking, subsidies – especially blanket subsidies for commodities – are not sound or sustainable policy. But in the push to reform or “rationalize” petrol subsidies, is it possible that some simpler measures have been overlooked? And is it possible that the most problematic issues around the subsidy (namely, large-scale cross-border smuggling) are being left unaddressed?

SMALL VENDORS FEELING THE HEAT

In a tale recounted in a recent article in the South China Morning Post, a street vendor in a Kuala Lumpur suburb flips appam on his sizzling wok while expressing mounting anxiety about the impending petrol subsidy overhaul. Since diesel support was withdrawn in June of last year, the cost of ingredients has already climbed, eating into his margins. Now he is bracing for the next wave of price increases if petrol subsidies are scrapped.

His story echoes similar concerns from countless small business operators – from food stall owners to gig workers and delivery riders – whose costs rise with every subsidy cut. Rising RON95 prices would cut into daily earnings, forcing many to make difficult choices between groceries, school fees and fuel costs.

Meanwhile, a veteran e-hailing driver, juggling long hours looking for passengers, warns that even a small price hike could turn a break-even day into a loss. He admits he might have to skip meals to cover the extra expenses that subsidy cuts are sure to bring. For drivers like him, the removal of the petrol subsidy means every ride becomes uphill in more ways than one.

Families with long commutes – those driving between Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya, or Klang and Petaling Jaya, for example – also face a double burden. They rely on stable petrol prices just to pay for child care and work travel. Once subsidies are gone, the ripple effect could reach food prices, transport costs, and even public budgets for essentials. Add to that the cost of tolls and parking, both of which have risen in the last few years, and suddenly, driving in Malaysia will become a lot more burdensome.

WHY REMOVE SUBSIDIES ALTOGETHER?

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has defended the plan as fiscally responsible. In October’s budget, he noted that blanket subsidies for petrol, electricity, and water were unsustainable and disproportionately benefitted the wealthy. (Left unsaid was the fact that the wealthy pay far, far more in taxes than the lowest tier of earners in Malaysia; in fact, those earning less than RM34,000 a year after EPF deductions pay no income tax at all.)

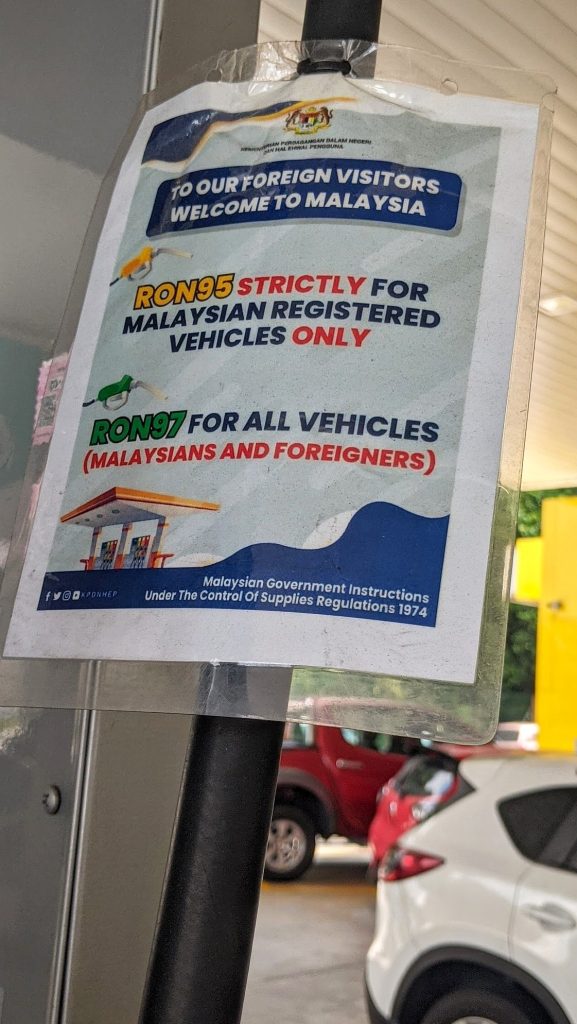

Anwar went on to claim that up to 40% of petrol subsidies – an estimated RM8 billion annually – goes to the top 20% of income earners, which includes “foreigners and the ultra-rich.” (How this figure could possibly be ascertained with any semblance of accuracy is unknown.) He further maintained that subsidy cuts were necessary because of the “four million foreigners in this country.”

He then argued, once again without explaining how these numbers were calculated, that eliminating subsidies for non-Malaysians could cut national spending by about RM8 billion, enough to fund education, healthcare, and public transport. He also pushed ideas like ID checks at petrol stations to restrict subsidized fuel sales to citizens.

Though publicly, the push to reform the subsidies appears to be moving along at full steam, all may not be what it seems. According to reporting in the South China Morning Post, the timing for such a move is politically fraught.

Public discontent is already on the rise, fuelled by growing accusations of nepotism linked to the political rise of Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Izzah, with the prime minister being hit by a blizzard of criticism of late, according to the SCMP.

“It is a very unpopular decision to make, regardless of who is in charge,” said Adib Zalkapli, managing director of geopolitical and public policy advisory firm Viewfinder Global Affairs, stating the obvious.

The SCMP article continues, saying, “The political risk appears to have rattled Anwar. After initially claiming last October that 85 percent of drivers would be unaffected by subsidy cuts, he has since widened that estimate. ‘I would like to reiterate that there is no issue of the RON95 increase affecting 85 to 90 percent of our people,’ he said on June 16.”

Some netizens have commented that if the rationalization plan really won’t affect 90% of the population, maybe there’s a better approach to take.

LOW-HANGING FRUIT: QUESTIONING THE FOREIGNER NARRATIVE

Malaysians routinely take to social media to bitterly complain about Singaporeans seen filling up their cars with subsidized Malaysian petrol before heading back home over the Causeway. And while their ire is understandable – nobody likes it when others don’t play by the rules – it’s also unlikely that the relatively few Singaporeans who are doing this are causing a huge problem when it comes to Malaysia’s annual subsidy bill. (More to the point, it’s baffling why Singaporeans don’t just fuel up with RON97 in Malaysia. It’s still vastly cheaper than petrol in their home country – RM3.18 vs RM9.55 as of this writing – and it’s perfectly legal for them to buy.)

So while the Singaporean narrative is at least easy to understand, the prime minister’s “four million foreigners in Malaysia” claim is far less clear. Government data from agencies like Immigration and the Expatriate Service Centre shows approximately 150,000 expatriate passes issued last year and about 2.5 million foreign workers holding valid permits. However, it’s a sure bet that the overwhelming majority of these workers do not own or drive private cars. Foreign labourers typically rely on public or employer-provided transport.

Even among the country’s relatively small pool of expatriates, not all choose to purchase and self-drive vehicles – they often use e-hailing, and some even walk or use public transit. It’s also fair to point out that expats working in Malaysia pay taxes here just like citizens, and contribute to the country’s economy just like citizens. In fact, the government’s own data show that while expats comprise just 1% of the country’s entire workforce, they contribute about RM75 billion to the Malaysian economy – almost 5% of the country’s GDP.

So, placing the blame on foreigners for the country’s large petrol subsidy bill feels like a little more like populist rhetoric rather than anything based in quantifiable fact. The simple truth is: the number of foreigners who both live and drive in Malaysia is very, very small when considered as a percentage of the country’s population – well under 1%, in fact. It’s incredibly hard to imagine that this small group is responsible for RM8 billion in annual fuel subsidies, which is the number Anwar claimed would be saved by disallowing this particular group from enjoying the subsidies.

WHAT ABOUT GRADUAL PRICE ADJUSTMENTS?

Targeted subsidy removal certainly makes sense on paper – but RON95 is used far more broadly in Malaysia than diesel, and the outright elimination of subsidies risks both economic turmoil and political backlash. A phased approach could ease the transition: for example, raise the RON95 price from RM2.05 to RM2.20, monitor inflation and public reaction for six months, then inch it up again to RM2.30. This method would still save billions over time, yet soften the immediate impact on households and businesses. And, it wouldn’t require all the convoluted implementation and enforcement mechanisms that targeted subsidies do.

The government maintains that 85–90% of Malaysians would feel little to no effect of targeted subsidy removal (once again, bringing into question why do it this way in the first place if the effect is really that limited) – but independent studies and consumer sentiment still point to unease across income groups. The removal of blanket diesel subsidies last year, for instance, came with sharp public criticism and rising living costs – and a political cost, too.

FOCUS ON SMUGGLING AT THE BORDER

Meanwhile, one of the most glaring threats to subsidy effectiveness remains at least somewhat unchecked: cross-border fuel smuggling. Despite diesel subsidies being withdrawn in June last year, Malaysian petrol remains far cheaper than in neighbouring Thailand – and smuggling has shifted to include RON95.

Thai police estimates suggest hundreds of thousands of litres per month are smuggled by syndicates using pickup trucks with modified tanks. Malaysian authorities themselves reported 46 petrol stations in Kelantan attracting frequent and repeated non-Malaysian purchases. In Perlis and Kedah, smugglers in modified vehicles ferry subsidized petrol across the Bangkok-to-Hat Yai corridor.

Before the blanket subsidies on diesel ended in June 2024, it was estimated that some 3 million litres of subsidized fuel were being smuggled out of Malaysia on a daily basis, the vast majority of which was diesel.

According to reports, many of the smuggling operations are run by Malaysian-based groups, often in collaboration with petrol station operators, transporters, or local insiders. Even though the financial incentives of diesel smuggling have been reduced, these syndicates still exploit fuel subsidies by repeatedly purchasing RON95 (often using modified vehicles with extra tanks) and transporting it across borders. (It’s worth noting that this very much local activity was costing the Malaysian government about RM4.5 million a day at its peak, which makes the tactic of pinning the blame on foreign residents even more ludicrous.)

Kelantan’s domestic trade ministry plans to install CCTV in border petrol stations to monitor for suspicious bulk purchases, but implementation remains slow and incomplete. The government has said that stopping smuggling is a high priority, and various measures – some more effective than others – have been put into place, but without strong enforcement measures, subsidy cuts at the pump may do little to stop this large-scale leak.

POLICY CONUNDRUM AHEAD

Malaysia’s subsidy reforms always see leaders stepping into a political minefield. Last year’s removal of diesel support defied expectations for an economic earthquake, yet still spurred backlash and sparked by-election losses for the ruling coalition. With a general election due by 2028, RON95 cuts must be handled with far more tact.

Political analysts say Anwar is walking a fine line: push too far and risk alienating both his core voters and the aspirational middle class; move too slowly and fail to stop the fiscal hemorrhage. That’s why many analysts argue for a mix of phased cuts, better enforcement against smuggling, and greater transparency over who really benefits.

We couldn’t agree more.