Are you haunted by images of “Jaws”? Scared of scuba? Nervous about even dipping your toes in the sea? Gordon Reid explains why it is, literally, safe to go (Back) in the water round Malaysia – and why it is worth doing so. He also has some surprising facts about who is really threatening whom.

Stephen Spielberg’s early blockbuster “Jaws”, with its graphic depiction of an enormous, vicious and even vengeful Great White shark, has a lot to answer for. It may not be the only reason that so many people are afraid of sharks, but it bears a fair share of the blame. My eldest son, young and impressionable when “Jaws” first came out, spent years after that refusing to step into any sea above waist depth (though he is now a keen scuba diver).

MYTHS AND REALITY

The biggest myth of all is that most, if not all sharks are potentially dangerous to humans: bloodthirsty killers waiting to pounce on their next meal of human flesh. The reality is very different. In fact, of more than 300 shark species worldwide, only four – yes, four – have been involved in any significant number of serious attacks on humans: the Great White, Tiger, Bull and Oceanic Whitetip sharks. None of these, by the way, are found in the coastal waters round Malaysia or the surrounding region.

Moreover, even those species responsible for the relatively few attacks that do occur do not generally target humans deliberately. We are not their prey of choice. Great Whites like Jaws, for example, eat seals – which are much fattier, juicier and more nutritious than we are! Most shark attacks are a case of mistaken identity (such as the frenetically paddling surfer who looks and sounds like an injured seal) or are caused by foolish human behaviour (such as “chumming”, or deliberately feeding sharks to lure them in – reportedly one of the causes of last year’s very unusual attacks by Oceanic Whitetips in the Red Sea). This explains why the vast majority of humans unlucky enough to be bitten by a shark live to tell the tale: once the shark discovers it has the wrong prey, it lets go. It also explains why divers quite frequently swim unprotected and unharmed with all the above species of shark, including even the infamous Great White.

These realities translate into statistics. Throughout the whole world, there are an average of only 70 or so shark attacks each year. Only a small proportion of these are fatal: less than five a year (4.3 to be exact) over the last ten years. Moreover, the bulk of these attacks happen around America, which has more than its fair share of aggressive shark species. The shark attack figures for Malaysia and this region are pretty reassuring.

Since records began over 100 years ago, there has only ever been one single – nonfatal – shark attack in Malaysia, while near neighbours Singapore (4), Indonesia (3) and Thailand (1) have recorded only a few more. Even based on the global figures, your chances of being killed by a shark are massively lower than of being drowned (3,000 times more), dying in a boating accident (300 times) or even being bitten to death by a dog (30 times)!

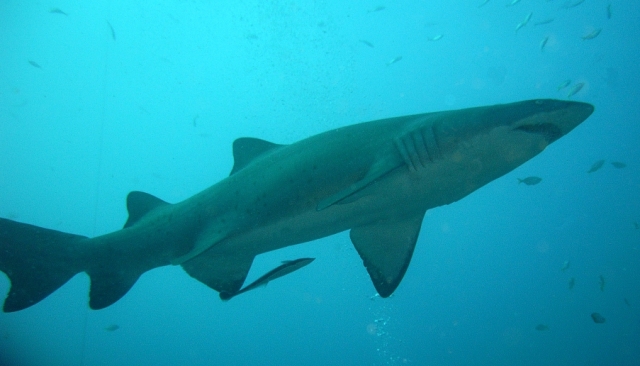

Scuba divers know this. In fact, most of us spend our time underwater actively looking for sharks. We want to see them – and in my case to photograph them – close up. This is no easy matter, because most of the species we encounter are quite shy and will swim away when divers approach. But luckily not always: take a look at the photos on these pages of Whitetip Reef sharks I got really close to on a recent dive-trip to Sipadan. And not a bite mark on me!

SHARKS OF MALAYSIA: WHAT AND WHERE?

So what sharks can you see around Malaysia? A wide variety. By far the most common, and easiest to spot, are the reef sharks. As their name suggests, these generally live in shallower water in and around coral reefs. They include the eponymous Whitetip, Blacktip and (bigger and rarer) Grey reef sharks. But also other reef inhabitants like Nurse sharks, which can be found cosily huddled together in groups under rocks during the day; and the small but cute Bamboo sharks. Oh, and I mustn’t forget the rather larger (2 metres plus) but absolutely docile spotted Leopard sharks with their long tapering tails.

But that’s not all. Malaysia’s waters are also visited by some even larger elasmobranches (to use the fancy scientific name for sharks and their close cousins, the rays). These include the weirdly shaped Hammerhead… and the enormous Whale shark, which at up to 12 metres in length is the world’s largest fish (but is also an extremely docile and harmless plankton eater).

WHERE CAN YOU FIND THESE FASCINATING CREATURES?

Well, almost all of the species I have mentioned can and do crop up at virtually all of Malaysia’s dive destinations. However, don’t expect to drop in the water and be instantly surrounded, Discovery Channel style, by a sea of sharks. Shark sightings are nowadays relatively rare, and not just in Malaysia. Moreover, they are getting rarer – see below for why. You can still expect to meet at least one or two of the more common reef sharks quite regularly around Malaysia’s East Coast islands (Perhentian, Redang, Tioman and so on). But if you want a good chance of seeing even bigger stuff, or of seeing sharks in concentrated numbers, you’ll need to go a bit farther afield to Sabah. Sipadan in particular (where I recently saw over 20 sharks in one dive!) is still a shark Mecca.

WHO’S THREATENING WHO?

So why are sharks getting rarer? Because these majestic creatures are being hunted down systematically by their one and only predator……man! Why do we do it? Mainly for their meat. Or rather (even worse) for a small part of their bodies: their fins, which are a key ingredient in that well known Asian delicacy, shark fin soup. Like many destructive human activities, when we do it, we do it big time. Estimates of the numbers of sharks caught and killed each year range from 50 to 100 million (yes, million). Rather more than the 4.3 humans killed each year by sharks!

This overfishing has led to a disastrous fall in shark populations. Some species have lost well over 90% of their numbers, and are already acutely endangered. Even less endangered species have seen numbers plummet.

Not only is shark finning (the still all too frequent practice of cutting off the fin and throwing the crippled shark back into the water to die) wasteful and cruel, but it risks depriving our seas of these elegant – and ecologically vital –creatures. As a result, divers and snorkellers like you and I will find it more and more difficult to get a glimpse of these beautiful animals. But even more serious, the decimation of these apex predators could have disastrous consequences for the ecological balance in our oceans.

So next time you are offered shark fin soup, please think hard…and (to borrow the anti-drug slogan) just say no!

Source: The Expat July 2011

This article has been edited for Expatgomalaysia.com

Get your free subscription and free delivery of The Expat Magazine.

"ExpatGo welcomes and encourages comments, input, and divergent opinions. However, we kindly request that you use suitable language in your comments, and refrain from any sort of personal attack, hate speech, or disparaging rhetoric. Comments not in line with this are subject to removal from the site. "