Tucked away along the coast of Melaka lies the Portuguese Settlement, one of the city’s most distinctive heritage enclaves. Established in the early 20th century, but rooted in a much older colonial history, this small coastal community still carries the traces of Portuguese life, where traditions, language, and food have blended into something unique.

This article contributed by Sabine Ferrão

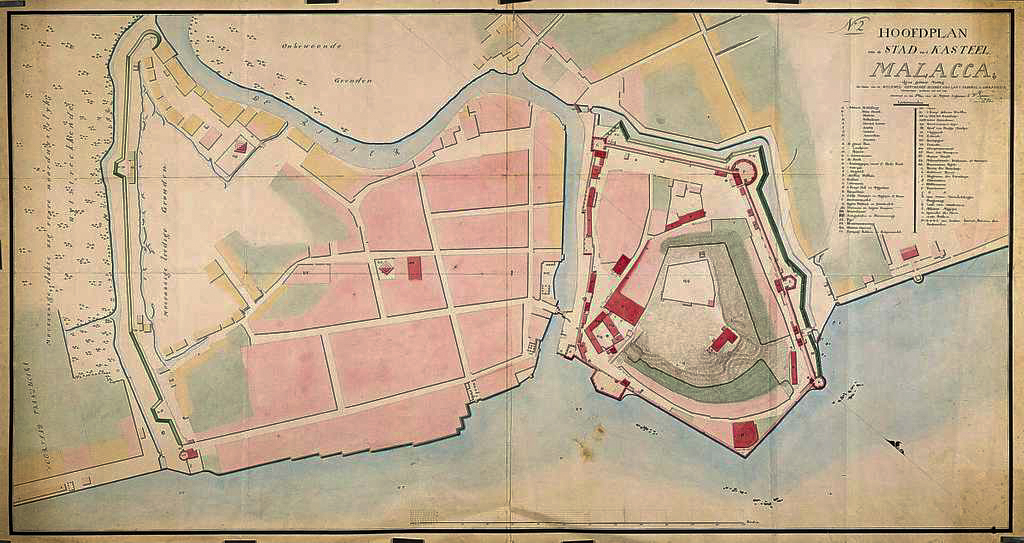

Portuguese explorers first arrived in Melaka (then Malacca) in the 16th century, leaving behind not only churches and fortresses, but also a lasting influence on language, food, music, and traditions. The first explorer to arrive in Melaka was Diego Lopes de Sequeira, on September 11, 1509, warmly welcomed by Sultan Mahmud, who reigned over Melaka. Captivated by the bustling port with its scent of spices and sweet tropical fruits, they established friendly ties through a treaty, with Rui De Araújo representing the Portuguese. However, envy among rival traders led to the Sultan being poisoned and De Araújo’s men imprisoned. In response, Afonso de Albuquerque sailed to Melaka in 1511, demanding their release. When diplomacy failed, he launched an attack that ended in Portuguese victory, marking the conquest of Melaka and the birth of a new mixed community, the Kristang or Melaka Portuguese.

A MULTICULTURAL POPULATION

Afonso de Albuquerque strengthened Portuguese control in Melaka by encouraging settlers to marry and integrate with the local community, offering land and livestock as incentives. The “Orfas Del Rei” programme brought orphaned Portuguese girls to wed settlers, while mixed-race children and converts were granted full citizenship. These policies fostered a loyal, multicultural population that upheld Portuguese influence. Under their rule, Melaka thrived as both a key trading hub and a centre for Christianity, visited by missionaries such as St. Francis Xavier in 1545. The Portuguese remained in power until 1641, when the Dutch takeover forced many settlers to retreat inland.

FAITH IN HIDING

When the Dutch took control of Melaka, their Calvinist beliefs led to strong intolerance toward the Portuguese Catholics and their local converts. Yet not all Dutch officials shared this stance. The first Dutch governor, Justus Schouten, recognized that harsh measures deepened unrest. Believing that peace and prosperity could only return if the people were allowed freedom of worship, he appealed to Batavia, where the regional colonial Dutch authorities resided, to relax the ban on Catholic practices, though his proposal came with strict conditions.

His more tolerant view was not widely supported. The Dutch Calvinists strongly opposed public Catholic worship, insisting on adherence to their own faith. In 1646, Jesuit priest Father Alexandre de Rhodes condemned this hypocrisy, pointing out that while other religions were free to maintain their temples, Catholics were forbidden to practise theirs.

Before long, Governor Bort enforced a directive that outlawed Catholic worship altogether, expelling Portuguese families who refused to embrace the Dutch Church. By then, fewer than 1,600 Portuguese settlers remained in Melaka.

SECRET NIGHT MASSES

Even so, the priests refused to abandon their flock. They ministered to their communities in secret, hiding in the jungles and venturing out under the cover of night to celebrate Mass. In a letter to Rome, Father Dominic Fernandez Navarette,described how, at eight o’clock in the evening, he was quietly guided upriver by the Brotherhood of the Rosary to where most Catholics lived. There, in the darkness, they sang hymns – “the most beautiful in the world,” he wrote – a testament to faith that refused to fade.

It was in the early 18th century that the Dutch began to ease their restrictions on the Portuguese Catholics, a turning point marked by the construction of St. Peter’s Church in 1710. This church still stands today as the oldest functioning Catholic church in Malaysia, a symbol of endurance and faith.

As conditions improved, many families gradually moved out of the swampy outskirts and back into town and its suburbs. Portuguese communities began to flourish once more in neighbourhoods such as Tranquerah, Banda Kaba, and Banda Hilir, blending harmoniously with Melaka’s multicultural population. Over time, their unique Creole language, Kristang, became so deeply woven into local life that even those outside the Portuguese community could speak and understand this melodic, centuries-old patois.

THE SETTLEMENT TAKES SHAPE

In the mid 1920s, a Portuguese mission priest realized a plight faced by the poor Portuguese

fishermen as their living conditions and economic affairs were desperate. Two priests, Fathers Coroado and François, along with Mr. V.E. Dias helped to obtain a piece of land from the British Colonial government at the foot of St John’s Hill. The land was a 28-acre swamp, and it required a lot of hard work to clear it for dwelling. The priests convinced a few fisherfolk this was an ideal place and situation for the community to call their own, where they could preserve and retain their identity through cultural beliefs, traditions, and customs. Furthermore, the seaside was ideal for the poor fishermen, where their boats could be docked safely, and they would no longer have to live in sheds along the beaches, constantly threatened by weather conditions.

The colonial government stepped in to help by offering cheap housing at a nominal rent, sparking the birth of a new community. By the early 1930s, the first 10 houses had been built, growing to 60 by the end of the decade, each one filled with families rebuilding their lives by the sea. As the settlement flourished, children began attending Catholic schools, encouraged by the devoted Brothers and convent Sisters who championed the community’s education and social well-being.

A THRIVING COMMUNITY TODAY

The vision once shared by the two priests who founded this settlement has truly come to life. Today, the community flourishes – proudly preserving its roots, culture, and centuries-old traditions. What began as a small, close-knit group has grown into a vibrant cultural landmark that now attracts visitors from far beyond Melaka’s shores.

The people who live here are descendants of the early Portuguese settlers who arrived in Melaka in 1511. Over the centuries, they have held steadfast to their faith and identity, enduring challenges that might have erased their heritage elsewhere. Thanks to their resilience and deep sense of belonging, the traditions of this unique community continue to thrive – proof that even in modern times, history can be very much alive. Once fugitives of a fallen colony, they now stand proudly as guardians of a living legacy.

Each year, the settlement bursts into colour and celebration during its two most significant festivals: Festa San Pedro in June (honouring St. Peter, the community’s patron saint) and Christmas. On these occasions, the neighbourhood transforms into a lively hub of music, dance, and festive cheer, with food stalls serving traditional dishes and streets decked in dazzling decorations. If you happen to be in Melaka in December, don’t miss the chance to wander through the Portuguese Settlement and be witness of a truly unique Christmas celebration that’s quite unlike any other in Malaysia.